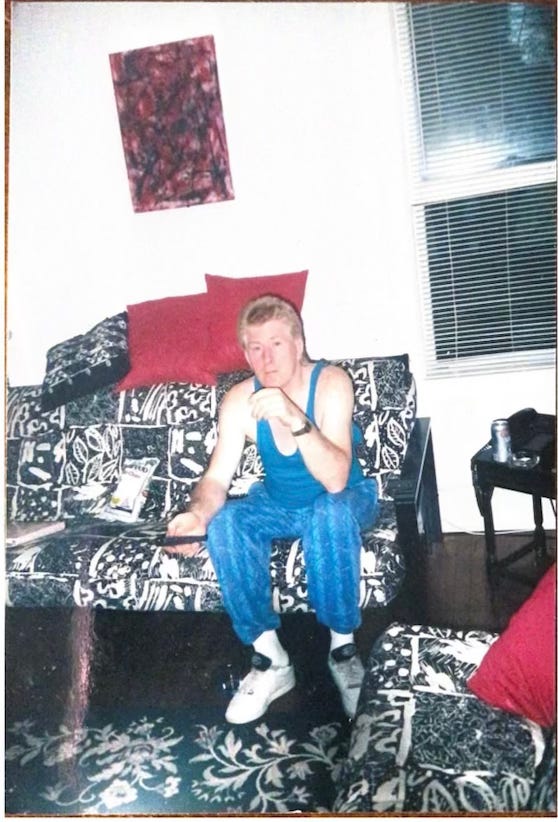

I remember most, his sweaty brown fingers and the way they’d hold a fag. The curl in his hips as he leant in the half-way of the porch door and the kitchen- always looking in, listening to everything. He always wore wrinkled shirts tucked into cargo pants- and with his flop of white hair and his thrilling red eyes- he was always like a beastly creature in disguise to me- like a lost wolf who had formed into a man.

As the kettle whistled he’d gather the porcelain mugs- a selection of charity shop ware with phrases like ‘in this family we love’. There’s nothing more special to me than the cheerful dance of making tea for your guests- and he loved it. The rare flash of a smile as he bounced on frail feet- the concentration- the head dipping into the front room- his finger counting us- and the biscuits he’d put on a small plate for us to eat. And just like that he’d disappear into the kitchen to read the broad papers.

I don’t remember when he died- or the way his skeleton started to rip out from under his skin- or the sadness that hung on the walls of that house after he passed.

His daughter would trample in and kick the chair back in a tussle and huff loudly with a story to tell- the drops of an Irish folktale about to spill out- what would it be today? You’ll never guess who I just saw- the description of how sickly they looked- how that it’s awful sad what happened- and the beautiful head nods and silly laughs spared at the cost of a stranger who would never know that they were food for an afternoon of howling.

I am losing the specifics of the small memories- the colours of their bedroom curtains- and the car parked in the driveway. The doorbell sound and the snap of the porch door. And even though I hang on- I know they are leaving me.

To be honest, I never really knew my grandad’s brother- only the few times we visited his house. I remember arguing with my mom saying how I wanted to stay at home.

I miss the culture of sitting in a small room in a small town in Ireland talking about someone I have never met and cracking jokes at their near demise. The hot tea cuffed in my hands and the warm rosy cheeks of my nan.

When I go home now I visit my grandparents house and I sit for a while and we drink tea and I watch as they grow. And every time it makes me sad.

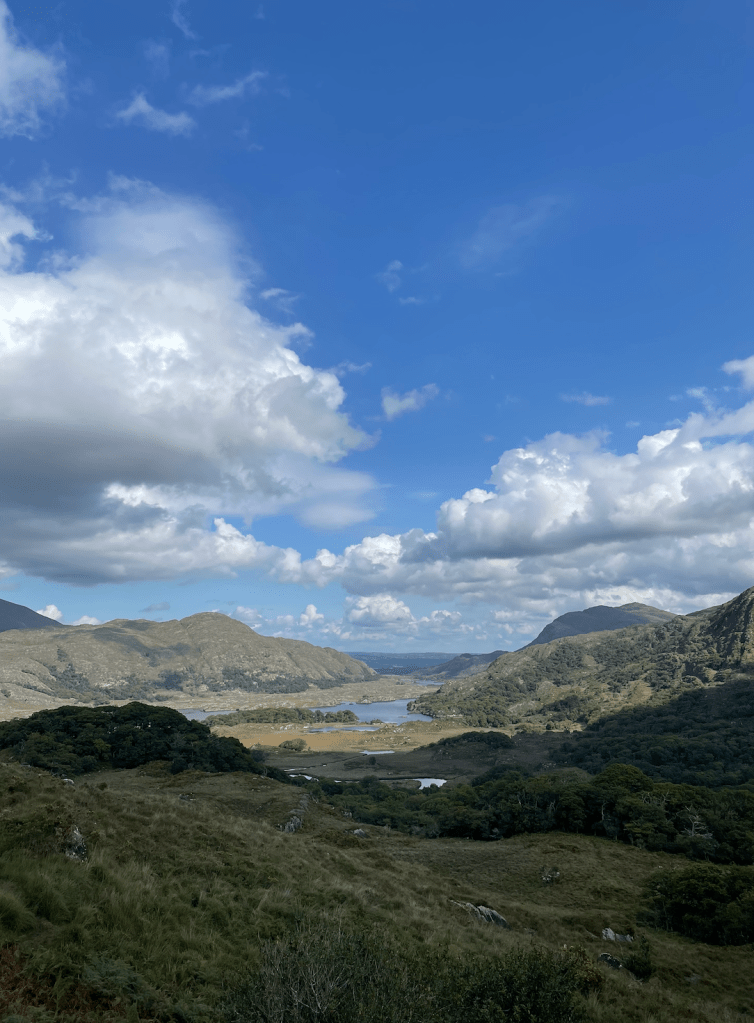

As I write alone in London, turning to look at the cold June sky, I think of home. I latch onto small memories- and they make me feel warm. The long car-rides home sitting in silence after a big fight with my mom, both of us sour with red faces. The smell of the burnt Sunday roast and the tinfoil wrapped around ugly plates, and my nan standing barefoot out the back smoking a fag- off balance and dejected- the weight of all her sufferings hanging from the clouds in the blue sky.

I click down the kettle as I look around an empty room of a house I will soon forget. And as the kettle whistles I experience the blaze of a home that is no longer mine. I think of the Excelsior can in my grandad’s hand and my nan’s fluffy housecoat.

I think of my grandad’s hand on my shoulder after reading my book- his fingers like shovels in mud. And I knew, even though he didn’t have the words to say it, that he was proud of me.

I search my mind for scents of homemade bread, the curly smoke coming from the burning end of my gran-uncle’s fag, and the image of my nan in the doorway watching our car leave- knowing she won’t see me for months.

I weep like the rain for the passing of mountains.

He stopped with a cheeky smile on him, and he said ‘now, one day that’ll be me that’s dead and gone- and you’d better be laughing at my downfall’.

Tears in our eyes, we did. We laughed, and we still do.